By Ray Paulick

Rick's Dream giving Bo Champlin his first win as an owner in 2019 © Benoit Photo

Bo Champlin was watching on television at his home in Visalia, Calif., when Rick's Dream and 11 other horses left the starting gate in the fourth race on the closing-day card at Del Mar on Sept. 7, 2020.

A California-bred gelding by Coil, Rick's Dream had given Champlin's Big Iron Racing its first winner nearly a year earlier when trainer Reed Saldana sent him out for an allowance/optional claiming victory at Santa Anita. Saldana and Champlin claimed Rick's Dream for $12,500 in his previous start at Del Mar in August 2019, and he was entered for a $10,000 tag at the seaside track just over one year later.

Early September is a busy time for Champlin, who grows alfalfa, corn, cotton, wheat, and pistachios on his 2,900-acre farm in the San Joaquin Valley. Visalia is located between Fresno and Bakersfield, about 300 miles north of Del Mar.

“I wasn't able to go down there for the race,” Champlin recalled. “It's a 4 ½- to seven-hour drive, depending on traffic, and it's just a busy time of year at the farm.”

Rick's Dream, sent off as the fourth betting choice at 5-1, raced just off the early leaders under jockey Heriberto Figueroa in the 6 ½-furlong test. When the field straightened away in the stretch Rick's Dream had about two lengths to make up, but something went amiss. Figueroa quickly pulled the horse up, and he was attended to by veterinarians and taken back to the stable area in the horse ambulance.

“I knew something was wrong,” Champlin said. “Reed texted right away and about 30 minutes later a veterinarian called, describing the injury.”

It was what Southern California veterinary surgeon, Dr. Ryan Carpenter, called a “typical fetlock breakdown,” an injury that for many years almost always led to the horse being euthanized – especially when that horse is a bottom-level claimer. When Santa Anita experienced a spike in racing and training fatalities in 2019 that would eventually lead to significant safety reforms in California and other racing jurisdictions, Carpenter said 19 of the 21 fatal injuries were fetlock fractures.

“That gave us a specific injury to target,” he said.

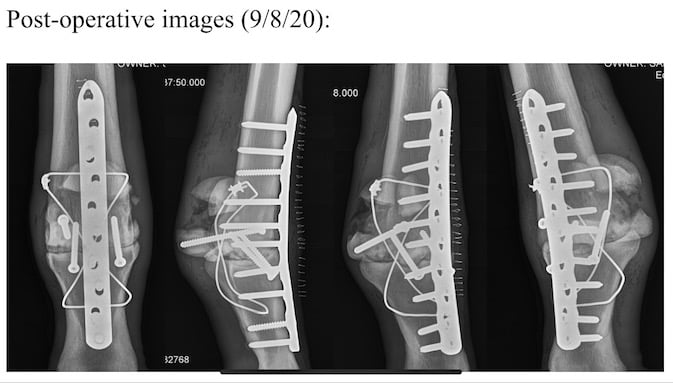

The attending veterinarian who called Champlin said Rick's Dream was a good candidate for a surgical procedure for fetlock injuries, arthrodesis, where sesamoid fractures are repaired by fusing the bones in the ankle joint with a metal plate and screws.

Radiographs of Rick's Dream following arthodesis surgery.

The surgery and rehabilitation can be expensive, Carpenter explained, costing from $20,000 to $30,000. Owners of a stallion prospect or a filly destined for the breeding shed can justify the expense from a financial standpoint, but that may be a different matter for a $10,000 claimer. The procedure leaves a horse pasture sound and comfortable, but the horse is left with a mechanical gait that will preclude it from having a second career as a sporthorse.

That's where the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club and Thoroughbred Owners of California come into the picture. Following a similar program launched in 2019 by Santa Anita and other tracks owned by The Stronach Group, Del Mar and TOC provide financial assistance for the type of surgeries that can save a horse from euthanasia and provide a good outlook for a life after racing.

“It's a cooperative deal between the track, TOC and the horse owners,” said Tom Robbins, Del Mar's executive vice president of racing. “Everybody takes part.”

Satisfied over the prospects that Rick's Dream could have a good quality of life, Champlin agreed to have the surgery done to try and save the horse that gave him and his family the thrill of their first win.

“I feel like if you're going to be in this sport, you've got to accept what happens and do the right thing,” Champlin said. “I felt it was the right thing to do.”

Rick's Dream became the first horse at Del Mar to have surgery funded jointly by the track, TOC, and an owner. Robbins said there have been four others since the program began in 2020, three which were injured during racing and one during training. Those low numbers reflect the success of initiatives by Del Mar and the California Horse Racing Board that make it one of safest tracks in North America.

Rick's Dream at his owner's farm in Visalia, CA

And how is Rick's Dream doing more than two years after the surgery?

“He's just a happy guy,” said Champlin, who quickly built a corral and barn and seeded a pasture on his farm while Rick's Dream was recovering from surgery at San Luis Rey Equine Hospital. “He rules the roost out here. Such a cool horse, though we've spoiled him a little bit.”

Rick's Dream shares a paddock with two goats and a longhorn steer, said Champlin. Irish-bred Liberal, another runner for Big Iron Racing, recently joined Rick's Dream in the paddock while getting some turn-out time away from the track.

“Dr. Carpenter and his staff have been really great,” Champlin added. “They really took a liking to the horse. He kept following up and following up to see how he was doing.”

If it weren't for a trip Carpenter took to the East Coast in 2017, the outcomes for this type of surgery would not be as successful.

Carpenter got a call from Paul Reddam after the California-based owner's Irap suffered an injury past the wire after finishing second in that year's Grade 1 Pennsylvania Derby. Reddam wanted Carpenter to fly east to perform surgery.

“The horse needed a fetlock arthrodesis,” Carpenter recalled. “I told him Dean Richardson was the best person to take him to.”

Richardson, the chief of large animal surgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine's New Bolton Center, is best known as the veterinarian who performed surgery on Barbaro and tended to the colt after he suffered a severe injury in the Grade 1 Preakness in 2006.

Reddam persisted, and Carpenter agreed to go in to surgery with Richardson, taking a red-eye flight that night and joining the surgical team the following morning.

“Dean certainly doesn't need my help, but from a personal and professional standpoint, this was the best continuing education I could ever have gotten in my career,” Carpenter said. “I had done this surgery before, but seeing the master at work and how he did things a little differently led me to change my style from the way it was.

“I credit that experience to why we have the success we have here today,” he said. “If I had stayed in California and not gone to see his work, I wouldn't have learned what I did.”

With Richardson now retired, Carpenter has been refining the fetlock arthrodesis surgeries in ways that avoid some post-surgical complications, including subluxation of the pastern. The latest improvement involves use of a human distal femur plate that incorporates the pastern. “We are not seeing the subluxation problems now,” Carpenter said. “This is going to have a positive impact on our profession moving forward.”

Not to mention the positive impact it has had on horses.

“The philanthropy of the racetracks and other stakeholders has allowed us to take finances out of the equation,” Carpenter said. “That permits us to make decisions based on what's in the best interest of the horse. The surgeries and techniques have advanced over the past 20 years to give these horses a chance for a successful outcome, keeping in mind the importance of their health and welfare. If it's good enough for a champion, it should be good enough for Rick's Dream.”